Many premium 3D printers include this feature standard, but fortunately it can also be installed on many lower cost 3D printers as an upgrade. Once you have all the options you want and your printer model setting uncommented now it’s time to make sure it compiles with no issues. To do that just click the ✓ at the firmware bottom-left of Visual Studio Code and it will build the firmware. The firmware update consists of downloading the firmware itself, opening it in Visual Studio Code, setting the options for your machine, compiling it, and then uploading it to the printer. If you start this routine, it will most probably first go to the corner nearest to the end stop of your printer. You can now visually determine if this position is at least in the ballpark of the correct one. As our experience in 3D printing grows with the passage of time, we may also get courageous enough to start tinkering with our hardware, install updates or set other start and end G-Code snippets.

For the actual data recovery, a spreadsheet was created to make an educated guess as to where the lost file should be. Starting at this address, about 90MB of data was copied into a new hex editor window. Because the SD card was plugged into a Mac before, a bunch of data was written on the card. This went into the first available place on the disk, which just happened to be the header of the lost MP3 file.

- Without pressing that big red Stop button, the file doesn’t close, and you’re left with a very large 0kB file on the SD card.

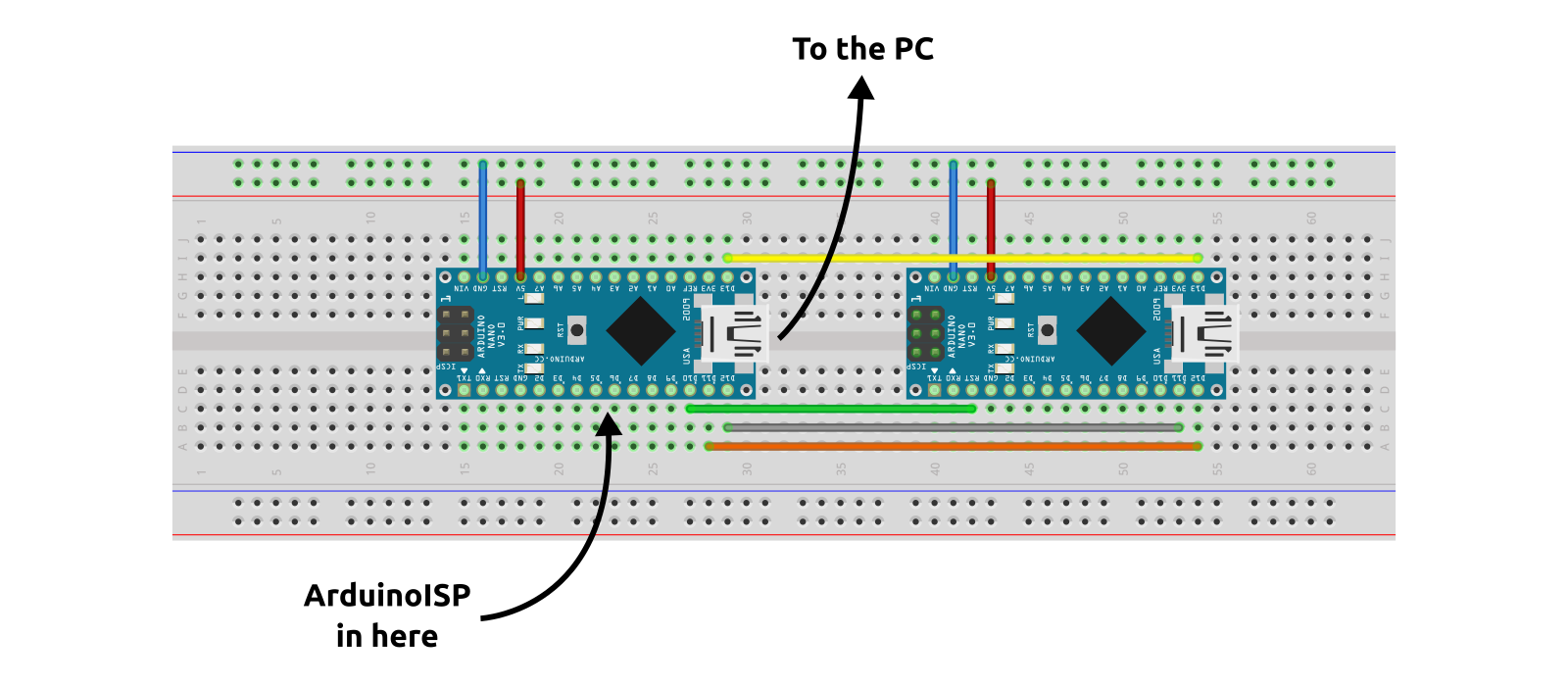

- Interrupting the flashing can “brick” your board and if this happens you will need to reflash the bootloader with a programmer before you can flash again.

- For all but the most specific forms of communication, just using “software” is usually fine.

- Fortinet devices receive constant firmware updates, so users always have the latest version.

It’s a binary format, might be called “.EEP” but might not. I’ve seen it used for ARM THUMB2 and for mystery stuff that may be a DSP/BSP. An integral part of doing embedded work is the build flow and system startup/booting procedure, plus getting your code onto the part.

Since the checksum is a two-digit hexadecimal value, it may represent a value of 0 to 255, inclusive. I’d compare the frequency (count for each value in the file) of instructions with the frequency of instructions derived from files for known processor types. That isn’t necessarily what your target wants to see, however.

Once you finished modifying the settings, you can click on “Sketch” and “Verify/Compile” right afterward. On the off chance that you own a CubeAnet8, an Anycubic 4MAX, a TronXY X5s, or an Anet AM8, you can download prepared firmware from this awesome website.